As I contemplated an article for this week (all my current ideas having failed to garner any inspiration), I got to thinking about legacies. Although the events of the past are set in stone, our perspectives on them and interpretations of them are forever evolving. This may be due to the unveiling of new historical records or archeological discoveries. But more often it is because we ourselves (as individuals or as a society) have changed and therefore view what came before in a different light.

Take for example Winston Churchill. His rallying of the British people through the dark days of the blitz during World War II with his rousing oratory and steely determination is heroic to say the least. Yet it is not too challenging to find fault with him. Certainly his once compatriots of the Liberal Party would’ve considered him a traitor when he switched to the Conservative Party. His Gallipoli operation in World War I was nothing short of a travesty and wasted life. To look at the changing attitudes of time, his belief in imperialism was largely the status quo for his era, but such views have become loathsome to most modern sentiments.

Or consider General George Patton. He was one of the great American heroes of World War II and was one of the few officers of any nation to truly understand the nature of mechanized warfare (though even he was surpassed by the lesser known General John Wood). His understanding of the operational art and drive as a leader was incredibly admirable. Yet he possessed a certain arrogance, not to mention his distasteful behavior in Sicily when he slapped a soldier suffering from what we now call PTSD. Even in his own era he faced condemnation for that.

For our final real world example, let’s look at Napoleon Bonaparte who is widely considered to be one of the Great Captains of history. He brought France to the apex of its power through a series of brilliantly executed campaigns. His skill on the battlefield set the standards for the conduct of war for decades and inspired two of the greatest works on the military art (by Clausewitz and Jomini). Nevertheless, he was a tyrant. He appointed his brother Louis as the King of Holland only to subsequently sack him because Louis had the gall to actually care about the Dutch. Napoleon wanted him to pillage the country, making it a slave state to France. Napoleon considered himself superior to everyone else and was furious that the Czar of Russia dared consider himself an equal. Though his skill on the battlefield was unmatched, Napoleon’s insatiable ambition is ultimately what destroyed him. He considered peace to be the first stage of his next war of conquest. He alienated friend and foe alike and, while he had the skill to defeat each of them in turn, by turning the world against him he sowed his own destruction. France after Napoleon was weaker than it had been before and at the cost of nearly a million French dead, not to mention the millions from other countries.

All three of these men are seen in both a positive and negative light with perceptions of them shifting over time. A generation from now, who knows how the world might view them. One doesn’t have to listen to much news these days to come across once-heroes vilified and once villains elevated. Yet even these new perceptions are still evolving. The person who was a hero in his lifetime may become a villain to the next generation only to return as a hero in the one after that. They have lived and died leaving any further condemnation or rehabilitation in our hands, not theirs.

So let’s shift this to fantasy literature.

One of the benefits of “Tears from Iron” and other such fictional works is that we come into close contact with the inner workings of the protagonist. We aren’t restricted to what Belarrin does and what he says. We can listen to his thoughts and feel the turmoil that rages in his heart. This is a luxury of the reader that isn’t available to Ninanna, Sravika, or Empress Kayrstana any more than you or I can be privy to Churchill’s inner struggles.

**********WARNING! This article includes spoilers. I strongly encourage that you only read this if you’ve finished “Tears from Iron.” This article includes spoilers concerning the heart of the story and may diminish the pleasure of discovery as you make your way through the novel.**********

Thus with Belarrin you, the reader, are witness to his many challenges, doubts, and fears as he shifted from a loyal t’Okaedrin to the champion of the rebellious Scions. You see his angst at the murders of Parvik and Vitarria. You see his struggles as he tries to reconcile how he was raised to what he realizes the world really is. You walk with him as he steadies the irascible Yrpel and defends the mild-mannered Zoltha. You feel his doubts in the face of the Shadow-Servant’s declarations and his ‘conversion’ to the other side. From there, you perhaps chafe as he wallows in indecision, trying to balance self and others and ultimately failing. You seethe in his helplessness as he’s forced to kill Zoltha and groan when he is bound upon the Boards. You rage with him at the murder of Talikae and revel in his furious vengeance. You feel his brokenness and the light of hope that follows with his redemption.

But such perceptions are unavailable to those around him. Inban condemned him as a traitor with good reason before his death. The Syraestari feared him and the threat he poised to their whole social order, hating his usurpation and wanting to destroy him. The Kalilaer of the smelting camp raised him up as a loyal friend and guardian, level-headed and sure. Sravika loved him for all these traits and more even while, in contrast, Kitiger cursed him for failing to protect the Scions. Nevertheless, he provided a path for both Hirnid and Talikae to claim the truth of their circumstances.

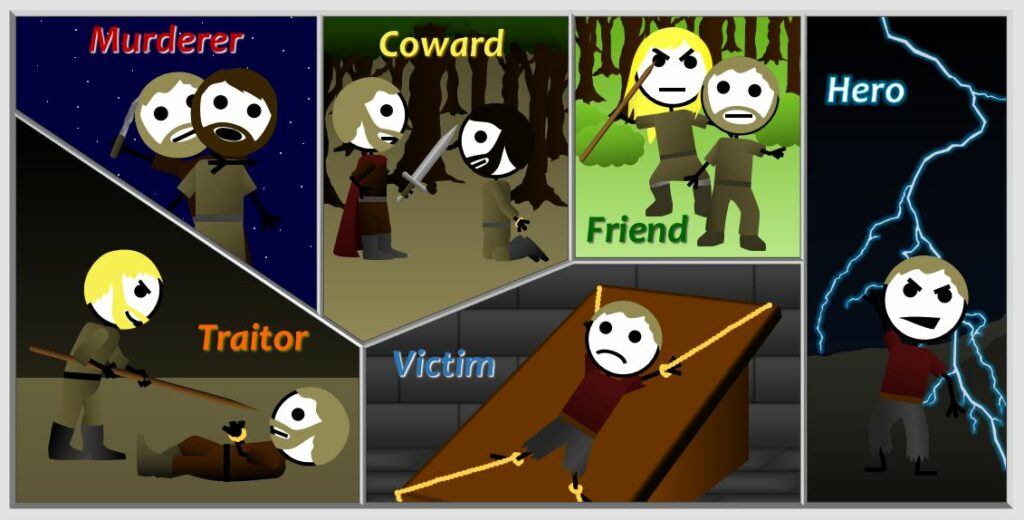

So who was he? Was he a traitor? A murderer? A coward? A victim? A friend? A hero?

You and I can see that he was all of these. Aren’t these all possibilities within ourselves as well, if not on so grand a stage? Yet the label applied to him by those who knew him depended as much upon their own perspectives as his actions. Such labels will continue to morph among future generations as societies evolve, rise, and fall. Indeed, each reader’s perspective will be different, too. The final conclusion on Belarrin as hero or villain will be based upon the weights applied for each good and bad action, the measure of belief in ends versus means, and the level of significance each of us applies to contrition and remorse.

I think perhaps the great lesson in this happens when we turn such truths back on ourselves. Do we truly understand those we praise and those we condemn? Are we looking at one small facet, interpreting it to our satisfaction, and then applying it to the whole? We have all been misunderstood at one point or another in our lives, often based upon a single word, expression, or deed. Do we truly want that one moment to encapsulate how we are defined, for better and for worse? I don’t know about you, but I am more complex than that. Those who seek to find my failings will succeed just as those who focus on my strengths will find those as well. But neither can tell the whole story. We are not a single stroke of the pen or a single moment in time. We are so much more than that.