The latest string of articles continues to evolve. We began with elves and the Aestari which included a discussion of good and evil. This led to talking about the nature of monsters and now, perhaps inevitably, we’ve moved on to villains. As we continue, I feel like I should further refine my definition of monsters from last article. This time, I am going to talk metaphysically rather than merely practically. The road may be a little long but it will lead to the promised villainy.

For purposes of this discussion, I consider monsters to be non-reasoning, non-sapient creatures. If a creature can reason, it isn’t a monster. Of course in our day to day parlance this is untrue. It is common to refer to our fellow humans as monsters. There is a serious danger in this because, in doing so, we dehumanize them.

Once something is dehumanized, it is reduced in value. It becomes a target for hate and persecution. As a prime example, look at the anti-Japanese propaganda posters of World War II which portrayed that people as sub-human. Or look at our world today. All you have to do is turn on the TV or check your favorite news feed. Take a look at any political, philosophical, or sociological dispute out there and I can almost guarantee that BOTH sides are referring to the other as monsters (or some other similarly dehumanizing term) as a means of advancing their cause. This is a method for dismissing anything that their opponents say, but intentional or not, it goes further. Once we dehumanize opposition in one way, it is only the slightest shift to do so entirely… they cease to be fellow humans and are reduced to soulless monsters. This opens the door to hatred (if that hasn’t occurred already) and atrocity. The point is this: Just because we may find a different perspective incomprehensible or even morally revolting, doesn’t mean that the person who holds it isn’t human. It doesn’t mean that they’re a monster that can only be met with the sword.

I may appear to have veered a bit off topic, here, but I don’t think so. This points to the potential argument that monsters may serve different definitions. After all, we might call Napoleon, Hitler, or Stalin monsters in our moral outrage. We may call those who commit violence today monsters for the same reason. But this labeling isn’t helpful because, in addition to what has already been discussed above, it denies us our capacity to try and understand them. By understand, I don’t mean agree or even tolerate. Evil should never be advocated or tolerated, but it should be understood. If we refuse to understand, we deny ourselves the capacity to learn what led them down the paths they took… and thus we will encounter others who take those paths again and again and again. Or, even worse, we will become that which we loath most.

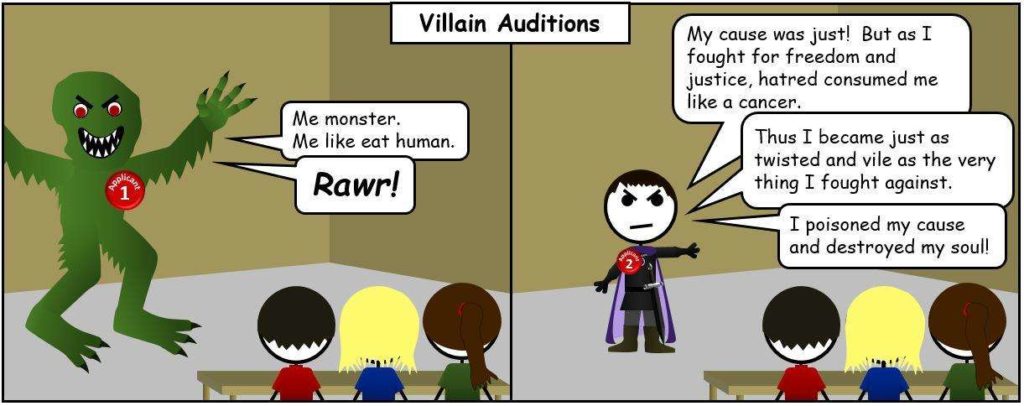

Okay, enough of the moral philosophy, what does this have to do with fantasy? It brings us back to a major point of my previous article: Monsters are too easy. That makes them poor villains.

“Easy?!?!” you might say. “But dragons can turn a village to ash in a single breath. A pack of dire wolves can make a trade route impassible. A troll under a bridge can deprive the nearby farmer of all his sheep! Dragons have near-impenetrable armored scales, dire wolves are cunning and vicious, while trolls are huge and regenerate wounds! Human enemies have got nothing on them.”

That is all true and is a reason that monsters can make useful obstacles in games. But that doesn’t make them the ideal challenge for a story. After all, the means to deal with such monsters is the same way you deal with pests in our own world (such as the gophers mentioned last article). You just need bigger, stronger, and more clever snares than your everyday pest controller… a magic endowed ballistae, for example, instead of a mouse trap.

This is where sapience comes in… because the best villains can think. The best villains have agendas of their own deeper than hunger, protection of a nest, or a predilection toward shiny things (okay, maybe that last one is true for both dragons and humans). And, “Hey,” you might argue, “Smaug was sentient!” That’s true, but was he really the villain of “The Hobbit”? If he were, the protagonist probably would’ve slain him. If he were, the scenes after his death would’ve been the resolution instead of the build up to the Battle of Five Armies.

Even more than that, the best villains have agendas that aren’t wholly evil… or at the very least, proceed from human motivations. Take the aforementioned Hitler and Stalin… horrible men who each murdered over ten million human beings… but neither did it out of a thirst for corpses or from a proclamation of their own villainy. They did it because they believed they were right (spoiler: they weren’t). They were each a product of their experiences (‘nature’ and ‘nurture’). In both their actions, we can see ongoing dangers that persist today. For example, both Nazism and Communism, the far right and the far left, crushed freedom of any speech and thought different from their own. It proved to be the most critical step to their relentless tyranny which serves as a warning to us today: the first step to oppression is to prohibit the speaking of words we don’t like. Once one voice is silence, the second is easier, and soon no one will be able to speak at all… including you. Unless, of course, you’re the villain in which case no one can speak but you.

Such extreme villainy can be potent, especially in epic world-spanning fantasy, but there is also value in a different kind of villainy. I’m not sure what to call it. “Lesser” came to mind, but I don’t want to diminish the experiences of those who endure it. Perhaps “personal” is better because it drives to the heart of an individual (or smaller group of people) rather than civilization itself.

Both kinds of villains are encountered in “Tears from Iron.” The next portion gives away parts of the plot. To avoid accidental spoilers, I’ve set the text and background to the same gray color. To read it, highlight the grayed out area with your mouse.

Ushtyl, the chief antagonist, is an example of the world-spanning villain. Much like Hitler or Stalin, he had a vision for how the world should be with the Syraestari as ultimate rulers and all other races subjected beneath them where they lived and breathed only for the good of their masters. But even more, he despised many of his own people and was willing to betray and murder anyone to achieve his ambition which was, of course, ultimate rule in his own hands. To his mind, no one else was worthy or capable enough.

Kayrstana might be seen as a world-spanning villain, too. After all, it was under her rule that humanity was enslaved. But within the confines of the novel itself, her villainous actions are more personal in nature. For example, she willingly sacrifices her loyal friend Ninanna strictly for political advantage.

Arcomin isn’t a world-spanning villain at all. His maltreatment of Belarrin and the Kalilaer in general is based on petty jealousy, insecurity, and vindictiveness. He is the quintessential bully.

But before we conclude, let’s jump back to monsters one more time. Are they useless? Do they serve no valuable role in a story since they simply are pests of a much more dangerous and fantastical variety? No, I believe they can still fill important purposes. In stories where the principal plot is “man versus self”, “man versus nature”, or “man versus God”, the need for a sapient antagonist may not exist. But if there is a sapient villain, the value in monsters is not in and of themselves. The value is in how it speaks to the villain’s purposes. In Tolkien, the thematic role of the orcs and goblins is less significant than how they exemplify the world that Sauron (and Morgoth) wish to rule. In Robert Jordan, the trollocs speak more to the Forsaken than themselves. The same is true with Lloyd Alexander’s Cauldron-Born.

Ultimately, I think the most important role of the villain is that he or she has the opportunity to speak to us about our own real world. Yes, the actions they take are often fantastical and impossible anywhere outside of the imagination, but their motivations to take those actions are not. Whether the villain be human, elf, goblin, or (sapient) dragon, the choices they make and the consequences they cause are human.